Anna Akhmatova: the fate of the famous poetess. All works by Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova; birth name - Anna Andreevna Gorenko; Russian Empire, Odessa; 05/30/1889 – 03/05/1966

Anna Akhmatova is one of the most famous Russian poets. During the writer’s lifetime, Akhmatova’s poems were published in many languages of the world, and the works themselves formed the basis of many musical works. Anna Akhmatova was one of the laureates at Nobel Prize in literature in 1965, but in her native country she was persecuted. Akhmatova’s poems were practically never published in the USSR, and to this day many people associate her name with persecution and repression during the Soviet Union.

Biography of Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreevna Gorenko was born in 1889 in Odessa. Her father was a mechanical engineer, and the girl herself was the third child in a family of six children. When the girl was only one year old, their entire family moved first to Pavlovsk and then to Tsarskoe Selo, where their father received a new position. Already at the age of five, the girl learned to read thanks to the alphabet, and soon she learned French, simply by watching the activities of older children.

When the girl was 10 years old, Anna Gorenko entered the Mariinsky Women's Gymnasium, and a year later she entered the Tsarskoye Selo Gymnasium. In 1906, she moved to Kyiv, where she entered the Kyiv Fundukleevsky Gymnasium, and in 1908 she studied at the Kyiv Higher Women's Courses. Here in Kyiv, on April 25, 1910, she married Nikolai Gumilev, whose works were already gaining popularity. Together with her husband, they founded the “Workshop of Poets,” which, in addition to the spouses themselves, includes several other aspiring poets.

In 1911, the first poems of Anna Akhmatova were published. They were published under a pseudonym at the request of the writer’s father, who asked not to disgrace his name. As a result, Anna took her grandmother’s surname as a pseudonym, and already in 1926, after a divorce from her second husband, she officially took the surname Akhmatova. Already in 1912, the couple had a son, who was named Leo. In the same year, the first collection of the “Workshop of Poets”, “Evening,” was published. In 1914, a collection of poems by Anna Akhmatova, “The Rosary,” was published, which was subsequently reprinted eight times. And in 1917, the third collection of Akhmatova’s works was published - “ White flock».

The year 1918 was a shock not only for all of Russia, but also for the poetess. This year she files a divorce from Nikolai Gumilyov and formalizes a marriage with the poet and translator Voldemar Shileiko. But after three years she separated from her second husband, although the divorce was officially formalized only in 1926. By the way, it was around this time that Akhmatova’s works almost completely disappeared from printed publications. In 1938, Akhmatova’s son, Lev Gumilev, was arrested. The events associated with this arrest were included in one of Akhmatova’s most famous poems, “Requiem,” which the poetess burned and rewrote many times. With the outbreak of World War II, she was evacuated from Leningrad to Tashkent, but returned back in 1944. After the war, Anna Akhmatova was subjected to severe criticism and stopped publishing. Only in 1951, thanks to her assistance, was her membership in the Writers' Union restored, and in 1958 her collection “Poems” was published. This was the last lifetime publication of Akhmatova's poems in Russia. In 1966, the poetess died and her son, Lev Gumilev, independently built her grave by collecting nearby stones.

Works by Anna Akhmatova on the Top Books website

Akhmatova’s poem “Requiem” is now so popular to read that the work was published in our winter of 2016. In addition, it was included in our ranking of the most popular books of the week several times. And given the growing interest in Akhmatova’s poem “Requiem,” we can assume that this work will appear in our subsequent ratings.

All poems by Anna Akhmatova

And you, my friends...

And you thought I was like that too...

And now you are heavy and sad...

And I go where nothing is needed...

A! It's you again...

White night

God's Angel, on a winter morning...

I used to be silent in the morning...

Was my blessed cradle...

He was jealous, anxious and gentle...

Through the Looking Glass

Every day there is one...

In poetry, everything should be out of place...

That night we went crazy with each other...

In Tsarskoye Selo

After all, somewhere there is a simple life...

Evening room

I see a faded flag above customs...

Once again given to me by napping...

Once again given to me by napping...

We are all hawkmoths here, harlots...

Everything promised it to me...

Everything has been taken away: both strength and love...

Everything was stolen, betrayed, sold...

High in the sky the cloud turned gray...

To the city of Pushkin

The Lord is unmerciful...

Yes, I loved them, those nightly gatherings...

You gave me a difficult youth...

Two poems

Twenty-one. Night. Monday…

The door is half open...

Exhausted by your long gaze...

The ancient city seemed to have died out...

We thought: we are beggars, we have nothing...

There is a cherished quality in the closeness of people...

The mysterious spring was still blooming...

I waited in vain for many years...

Living like this is free...

Spell

Tear-stained autumn, like a widow...

Here Pushkin's exile began...

Hello! You hear a slight rustling...

Earthly glory is like smoke...

And into a secret friendship with a high...

And now I’m left alone...

And when they cursed each other...

And the boy who plays the bagpipes...

And all day long, afraid of my own moans...

I will take this day out of your memory...

Caucasian

Every day is a new worry...

Like a white stone...

As a bride, I receive...

You drink my soul like a straw...

If only you knew from what kind of rubbish...

When a person dies...

Somehow we managed to separate...

Summer garden

Love conquers deceitfully...

The boy told me...

Mayakovsky in 1913

He left me on the new moon...

To me more legs no need for mine...

I have fun drunk with you...

My husband whipped me with a patterned...

Courage

Murka, don’t go, there’s an owl...

We don't know how to say goodbye...

On the threshold of white paradise...

Ice is growing on the glass...

There is a row of small rosary beads on the neck...

Freshness of words for us...

You can't confuse real tenderness...

Let's not drink from the same glass...

I am not with those who abandoned the earth...

Don’t frighten me with a terrible fate...

Unprecedented autumn...

Oh no, I didn't love you...

I rarely think about you...

Oh, life without tomorrow!..

One goes straight...

Trenches, trenches - you'll get lost here!..

It goes on forever...

He loved...

They are flying, they are still on the road...

“Unforgettable dates” have arrived again...

Leave me, and I was like everyone else...

From your mysterious love...

Along the hard ridge of a snowdrift...

In memory of Sergei Yesenin

The memory of the sun in the heart is weakening...

First comeback

The first long-range one in Leningrad

Before spring there are days like this...

Song of Peace

Song of the last meeting

St. Petersburg in 1913

Petrograd, 1919

A stranger's prisoner! I don’t need someone else’s...

Dry lips tightly closed...

I won’t say a word to anyone for a week...

Along the hard ridge of a snowdrift...

It’s hot under the canopy of the dark barn...

Came up. But he didn’t show his excitement...

Imitation of I.F.Annensky

Late reply

Pray for the poor, the lost...

After the wind and frost it was...

Last day in Rome

Afterword

Poem without a hero

Wild honey smells like freedom...

Primorsky Victory Park

Come see me...

I accompanied my friend to the front...

Ice floes float by, ringing...

Wake up at dawn...

Five years have passed...

May someday children read my name in a textbook

Native land

From an airplane

I didn't receive any letters today...

Heart to heart is not chained...

Gray-Eyed King

She clasped her hands under a dark veil...

He said that I have no rivals...

Glory to you, hopeless pain!..

The smell of blue grapes is sweet...

Like an angel stirring the waters...

The house immediately became quiet...

Secrets of the craft

This is how dark souls fly away...

Now no one will listen to songs...

The river flows...

What I do...

That city that I loved since childhood...

Three autumns

She came to torture me three times...

You are always mysterious and new...

You know, I'm languishing in captivity...

You are with me again, friend autumn...

You are my letter, dear, don’t crumple...

You came to console me, darling...

I marked it with charcoal on the left side...

Do you want to know how it all happened?..

To the artist

Tsarskoye Selo statue

For a whole year you have been inseparable from me...

Why is this century worse?..

The road to the seaside garden turns black...

Reading Hamlet

What about war, what about plague?..

Cast iron fence...

Wide and yellow evening light...

The gaps in the garden have been dug...

This meeting is not praised by anyone...

This is neither old nor new...

It's simple, it's clear...

I invited death dear...

I live like a cuckoo on a clock...

I know I can't move...

I cried and repented...

I learned to live simply and wisely...

I'm not asking for your love...

I didn’t cover the window...

I came to visit the poet...

I came here, a slacker...

I hear...

I've gone crazy, oh strange boy...

I asked the cuckoo...

I stopped smiling...

The review itself is angry and envious, with a pretense of objectivity in assessing people who accidentally became the parents of a great Russian poet.

The large parental family of Anna Akhmatova (nee Gorenko) looked somewhat strange in the eyes of her contemporaries. There was no special order and discipline on the part of the mistress in managing the servants (all the servants did what they wanted, and not what they were supposed to), the always confused mother-housewife managed the house very ineptly, wandered around the house all day long or beat her with knuckles nervous trembling of fingers on the table; Anna herself, her older sister and little brother, it seemed, his entire childhood and adolescence were also left to their own devices. Both girls - Anna and Inna - wrote poetry since childhood, but in their home there was no cult of literature; no one in the house particularly read books and did not start a personal library, as was customary in noble houses.

Anna and Inna were also sick with tuberculosis, while Anna also suffered from inexplicable sleepwalking. The father who abandoned the family, who squandered his wife’s large fortune, the lack of their own home and the Gorenko family’s eternal wanderings in the corners of the houses of their relatives - all this made their life unsettled and the family dysfunctional.

Anna's mother, Inna Erasmovna, was remembered by family friends for her meek kindness and courtesy, friendliness, and even for the fact that all her life she dressed without polish or taste, like an old woman: either like a landowner, or like a monk. But this was a well-born noblewoman, the heiress of a huge parental fortune, who mediocrely squandered it on her husband’s entertainment.

During her youth, Inna Erasmovna lent money to an extremist circle of revolutionary friends who were preparing an assassination attempt on the Tsar. In her youth, she had a protest character, kept up with her times, studied at the Higher Women's Courses against her father's will, and used cosmetics that were forbidden in those years.

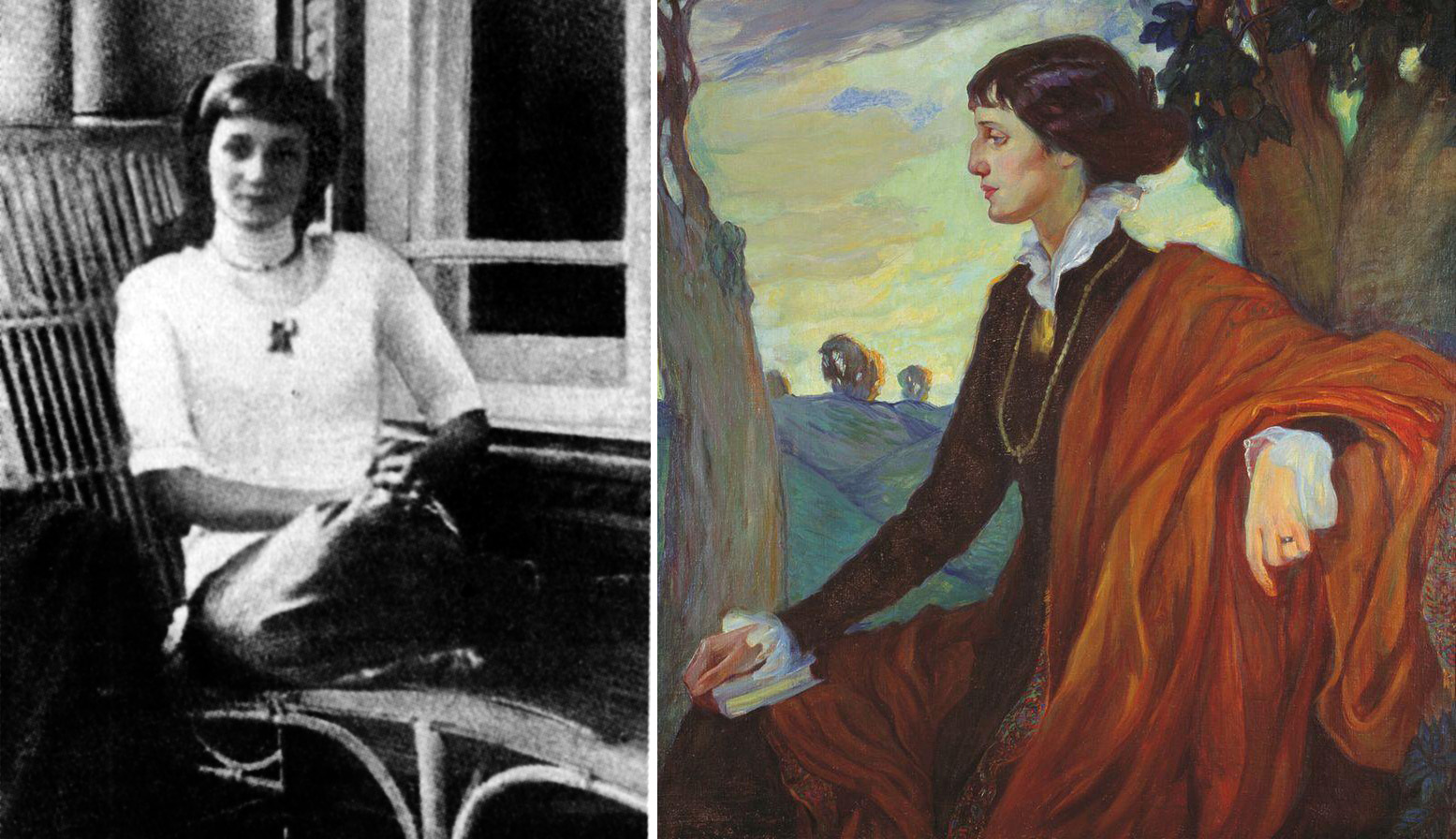

Photo:

Where did all this seething young nature of hers, protesting against philistinism, go after her second marriage to Andrei Antonovich Gorenko? Unlucky female lot constant betrayals her husband, his extravagance, and the lifelong illnesses of her children apparently broke this energetic nature and turned her into a confused and prematurely aged woman.

Anna Akhmatova herself, when asked by her friends why her mother was dressed so strangely, jokingly answered that her mother always had some kind of straps hanging over the back of her clothes, she couldn’t live without them.

Anna's father, Andrei Antonovich Gorenko, also in his youth was related to the terrorist organization "People's Will" and was closely acquainted with one of the developers of the bomb to kill the Tsar. For this acquaintance, he was recorded as unreliable by the tsarist secret police and expelled from naval service to civilian service.

Apparently, connections with the revolutionary circle introduced Anna’s future parents and made them friends. Black-haired young widow Inna Erasmovna, having met a young naval officer Andrei Gorenko, immediately fell madly in love with him and was unable to refuse her lover and colleague a small favor - giving about 2 thousand rubles to his friends to make a bomb.

Fortunately for both, this story ended for them without particularly tragic consequences, except for the forced resignation of Andrei Gorenko from naval service (but the creator of the bomb himself, a mine engineer and their comrade Nikitenko, was executed in the courtyard of the Peter and Paul Fortress).

Later, Andrei Antonovich Gorenko would become famous in his circle as a ladies' man and a ladies' man, a lover of theater and pretty women, who, without remorse, easily and beautifully squanders his fortune rich wife Inna Erasmovna. He will live with his family until the unfortunate and weak-willed wife runs out of money, and then he will abandon the impoverished Inna Erasmovna and his many children to the mercy of fate and marry another person.

Photo:

The most interesting thing is that, having a very dubious reputation in the world as a waster of life and red tape, Andrei Antonovich was very concerned about the honor of his family name and strictly forbade young Anna to publish her poems under the name Gorenko. He was oppressed by the fear that, in connection with his daughter’s poetic talent, people would “trash” his name! Thus, the father’s veto on his own surname became one of the reasons for the appearance in Russian poetry of the poet not Anya Gorenko, but Anna Akhmatova.

The history of the Gorenko family, despite the birth of a genius of Russian literature in it, is very sad and humanly evokes compassion.

The early death of one of the daughters - Inna - from tuberculosis, the departure of the husband (the father of the family) to another woman, his new marriage, the illness of his daughter Anna (her attacks of sleepwalking and tuberculosis), disappearance after the revolution youngest son Victor (whom all family members considered dead), lack of means of living, eternal homelessness, the failed marriage of Anna’s daughter with Nikolai Gumilyov, Anna’s single motherhood - these are the life trials that Inna Erasmovna had to overcome in her old age, as if as a punishment for her carelessness and illegibility in people. These are the life circumstances that made the Gorenko family vulnerable and dysfunctional.

But despite these troubles, Anna herself always maintained a royal posture; She behaved proudly and independently, helped her aging mother as best she could, and increased her poetic skills. And this family, as can be seen from the remark given at the beginning of the article, was even envied by some; those who were more well-fed and prosperous were jealous, they envied Anna’s creative successes and considered her disorderly family unworthy of the birth of such talent.

But, as they say, God has his own plans for everyone!

Photo: ru.wikipedia.org

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova

(surname at birth - Gorenko; June 11, 1889, Odessa, Russian Empire - March 5, 1966, Domodedovo, Moscow region, RSFSR, USSR) - one of the largest Russian poets of the 20th century, writer, literary critic, literary critic, translator.

The poet's fate was tragic. Although she herself was not imprisoned or exiled, three people close to her were subjected to repression (her husband in 1910-1918 N.S. Gumilyov was shot in 1921; Nikolai Punin, her life partner in the 1930s, was arrested three times , died in a camp in 1953; only son Lev Gumilyov spent more than 10 years in prison in the 1930s-1940s and in the 1940s-1950s). The grief of the widow and mother of imprisoned “enemies of the people” is reflected in one of Akhmatova’s most famous works, the poem “Requiem.”

Recognized as a classic of Russian poetry back in the 1920s, Akhmatova was subjected to silence, censorship and persecution; many of her works were not published not only during the author’s lifetime, but also for more than two decades after her death. Even during her lifetime, her name was surrounded by fame among wide circles of poetry admirers both in the USSR and in exile.

Biography

Akhmatova was adjacent to Acmeism (collections “Evening”, 1912, “Rosary”, 1914). Loyalty to the moral foundations of existence, psychology feminine feelings, understanding of the national tragedies of the 20th century, coupled with personal experiences, attraction to classic style poetic language in the collection “The Running of Time. Poems. 1909-1965". Autobiographical cycle of poems “Requiem” (1935-1940; published 1987) about the victims of repression of the 1930s. In “Poem Without a Hero” (published in full 1976) there is a recreation of the “Silver Age” era. Articles about the Russian poet Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin.

Family. Childhood. Studies. Anna Akhmatova born June 23, 1889, in Bolshoy Fontan, near Odessa. Her ancestors on her mother’s side, according to family legend, went back to the Tatar Khan Akhmat. His father was a mechanical engineer in the navy and occasionally dabbled in journalism. As a child, Akhmatova lived in Tsarskoe Selo, where in 1903 she met Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev and became a regular recipient of his poems. In 1905, after her parents’ divorce, she moved to Evpatoria. In 1906-1907, Anna Andreevna studied at the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium in Kyiv, in 1908-1910 - at the law department of the Kyiv Higher Women's Courses. Then she attended N.P. Raev’s women’s historical and literary courses in St. Petersburg (early 1910s).

Gumilev. In the spring of 1910, after several refusals, Anna Akhmatova agreed to become Gumilyov’s wife (in 1910-1916 she lived with him in Tsarskoye Selo); V honeymoon made her first trip abroad, to Paris (she visited there again in the spring of 1911), met Amedeo Modigliani, who made pencil portrait sketches of her. In the spring of 1912, the Gumilevs traveled around Italy; their son Lev was born in September. In 1918, having divorced Gumilev (the marriage actually broke up in 1914), Akhmatova married Assyriologist and poet Vladimir Kazimirovich Shileiko (real name Voldemar).  Anna Akhmatova's first publications. First collections. Writing poetry from the age of 11 and publishing from the age of 18 (the first publication was in the Sirius magazine published by Gumilyov in Paris, 1907), Akhmatova first announced her experiments to an authoritative audience in the summer of 1910. Defending from the very beginning family life spiritual independence, Anna made an attempt to get published without the help of Gumilyov - in the fall of 1910 she sent poems to V. Ya. Bryusova in “Russian Thought”, asking whether she should study poetry, then gave poems to the magazines “Gaudeamus”, “General Journal”, “Apollo” ”, who, unlike Bryusov, published them. Upon Gumilyov’s return from his African trip, Akhmatova reads to him everything he had written over the winter and for the first time received full approval for her literary experiments. From that time on, she became a professional writer. Her collection “Evening,” released a year later, gained very early success. In the same 1912, participants had recently

Anna Akhmatova's first publications. First collections. Writing poetry from the age of 11 and publishing from the age of 18 (the first publication was in the Sirius magazine published by Gumilyov in Paris, 1907), Akhmatova first announced her experiments to an authoritative audience in the summer of 1910. Defending from the very beginning family life spiritual independence, Anna made an attempt to get published without the help of Gumilyov - in the fall of 1910 she sent poems to V. Ya. Bryusova in “Russian Thought”, asking whether she should study poetry, then gave poems to the magazines “Gaudeamus”, “General Journal”, “Apollo” ”, who, unlike Bryusov, published them. Upon Gumilyov’s return from his African trip, Akhmatova reads to him everything he had written over the winter and for the first time received full approval for her literary experiments. From that time on, she became a professional writer. Her collection “Evening,” released a year later, gained very early success. In the same 1912, participants had recently  The so-called “Workshop of Poets” (Akhmatova was elected its secretary) announced the emergence of the poetic school of Acmeism.

The so-called “Workshop of Poets” (Akhmatova was elected its secretary) announced the emergence of the poetic school of Acmeism.

Under the sign of growing metropolitan fame, Akhmatova’s life passed in 1913: Anna spoke to a crowded audience at the Higher Women’s Courses, her portraits were painted by artists, and poets addressed her with poetic messages. New, more or less long-term intimate attachments of Akhmatova arose - to the poet and critic N.V. Nedobrovo, to the composer A.S. Lurie and others. In 1914, Anna Akhmatova’s second collection, “The Rosary” (reprinted about 10 times), brought her All-Russian fame, which gave rise to numerous imitations, which established the concept of “Akhmatov’s line” in the literary consciousness. In the summer of 1914, Akhmatova wrote the poem “Near the Sea,” which goes back to her childhood experiences during summer trips to Chersonesus near Sevastopol.

"White Flock". With the outbreak of World War I, Anna Akhmatova sharply limited her public life. At this time she suffered from tuberculosis, a disease that did not let her go for a long time. In-depth reading of the classics (A.S. Pushkin, Evgeniy Abramovich Baratynsky, Jean Racine, etc.) affects her poetic manner, the acutely paradoxical style of cursory psychological sketches gives way to neoclassical solemn intonations. Insightful criticism discerns in her collection “The White Flock” (1917) a growing “sense of personal life as a national, historical life.” Inspiring an atmosphere of “mystery” and an aura of autobiographical context in her early poems, Anna Andrevna introduced free “self-expression” as a stylistic principle into high poetry. The apparent fragmentation, disorganization, and spontaneity of lyrical experience are more and more clearly subordinated to a strong integrating principle, which gave Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky a reason to note: “Akhmatova’s poems are monolithic and will withstand the pressure of any voice without cracking.”

Post-revolutionary years. The first post-revolutionary years in Anna Akhmatova’s life were marked by hardships and complete separation from the literary environment, but in the fall of 1921, after the death of Blok and the execution of Gumilev, she, having parted with Shileiko, returned to active work - participated in literary evenings, in the work of writers’ organizations, and published in periodicals . In the same year, two of her collections were published - “Plantain” and “Anno Domini. MCMXXI". In 1922, for a decade and a half, Akhmatova united her fate with art critic Nikolai Nik  Olaevich Punin.

Olaevich Punin.

Years of silence. "Requiem". In 1924, Akhmatova’s new poems were published in last time before a multi-year break, after which an unspoken ban was placed on her name. Only translations appeared in print, as well as an article about Pushkin’s “The Tale of the Golden Cockerel.” In 1935, her son L. Gumilev and Punin were arrested, but after Akhmatova’s written appeal to Stalin they were released. In 1937, the NKVD prepared materials to accuse her of counter-revolutionary activities; in 1938, Anna Andreevna’s son was arrested again. The experiences of these painful years, expressed in poetry, made up the “Requiem” cycle, which the poetess did not dare to record on paper for two decades. In 1939, after a half-interested remark from Stalin, publishing authorities offered Anna a number of publications. Her collection “From Six Books” was published, which included, along with old poems that had passed strict censorship selection, new works that arose after many years silence. Soon, however, the collection was subjected to ideological criticism and removed from libraries.

War. Evacuation. In the first months of the Great Patriotic War Anna Akhmatova wrote poster poems. By order of the authorities, she was evacuated from Leningrad before the first winter of the siege; she spent two and a half years in Tashkent. She wrote many poems and worked on “Poem without a Hero” (1940-1965), a baroque-complicated epic about the St. Petersburg 1910s.

Resolution of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks of 1946. In 1945-1946, Anna Andreevna incurred the wrath of Stalin, who learned about the visit of the English historian Isaiah Berlin to her. The Kremlin authorities made her, along with Mikhail Mikhailovich Zoshchenko, the main object of party criticism; the resolution of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, “On the magazines “Zvezda” and “Leningrad” (1946), directed against them, tightened the ideological dictate and control over the Soviet intelligentsia, misled by the emancipating spirit national unity during the war. There was a publication ban again; an exception was made in 1950, when Akhmatova imitated loyal feelings in her poems written for Stalin’s anniversary in a desperate attempt to soften the fate of her son, in once again subjected to imprisonment.

Last years of life. IN last decade In the life of A. Akhmatova, her poems gradually, overcoming the resistance of party bureaucrats and the timidity of editors, come to a new generation of readers. In 1965, the final collection “The Running of Time” was published. In her dying days, she was allowed to accept the Italian Etna-Taormina Literary Prize (1964) and an honorary doctorate from Oxford University (1965).  Creative activity

Creative activity

One of the most talented poetesses of the Silver Age, Anna Akhmatova, lived a long life, full of both bright moments and tragic events life. She was married three times, but did not experience happiness in any marriage. She witnessed two world wars, during each of which she experienced an unprecedented creative surge. She had difficult relationships with his son, who became a political repressant, and until the end of the poetess’s life he believed that she chose creativity over love for him.

Anna Andreeva Gorenko was born on June 11, 1889 in Odessa. Her father, Andrei Antonovich Gorenko, was a retired captain of the second rank, who, after finishing his naval service, received the rank of collegiate assessor. The poetess's mother, Inna Stogova, was an intelligent, well-read woman who made friends with representatives of the creative elite of Odessa. However, Akhmatova will have no childhood memories of the “pearl by the sea” - when she was one year old, the Gorenko family moved to Tsarskoe Selo near St. Petersburg. Since childhood, Anna was taught  French and social etiquette, which was familiar to any girl from an intelligent family. Anna received her education at the Tsarskoye Selo women's gymnasium, where she met her first husband Nikolai Gumilyov and wrote her first poems. Having met Anna at one of the gala evenings at the gymnasium, Gumilyov was fascinated by her and since then the fragile dark-haired girl has become a constant muse of his work.

French and social etiquette, which was familiar to any girl from an intelligent family. Anna received her education at the Tsarskoye Selo women's gymnasium, where she met her first husband Nikolai Gumilyov and wrote her first poems. Having met Anna at one of the gala evenings at the gymnasium, Gumilyov was fascinated by her and since then the fragile dark-haired girl has become a constant muse of his work.

First verse Akhmatova composed it at the age of 11 and after that she began to actively improve in the art of versification. The poetess's father considered this activity frivolous, so he forbade her to sign her creations with the surname Gorenko. Then Anna took maiden name his great-grandmother - Akhmatova. However, very soon her father completely ceased to influence her work - her parents divorced, and Anna and her mother moved first to Yevpatoria, then to Kyiv, where from 1908 to 1910 the poetess studied at the Kyiv Women's Gymnasium. In 1910, Akhmatova married her longtime admirer Gumilyov. Nikolai Stepanovich, who was already quite famous person in poetic circles, contributed to the publication of his wife’s poetic works. Akhmatova’s first poems began to be published in various publications in 1911, and in 1912 her first full-fledged poetry collection, “Evening,” was published. In 1912, Anna gave birth to a son, Lev, and in 1914 fame came to her - the collection “Rosary Beads” received good reviews critics, Akhmatova began to be considered a fashionable poetess. By that time, Gumilyov’s patronage ceases to be necessary, and discord sets in between the spouses. In 1918, Akhmatova divorced Gumilev and married the poet and scientist Vladimir Shileiko. However, this marriage was short-lived - in 1922, the poetess divorced him, so that six months later she would marry art critic Nikolai Punin. Paradox: Punin will subsequently be arrested almost at the same time as Akhmatova’s son, Lev, but Punin will be released, and Lev will go to prison. Akhmatova’s first husband, Nikolai Gumilev, would already be dead by that time: he would be shot in August 1921.  Latest published collection Anna Andreevna dates back to 1924. After this, her poetry came to the attention of the NKVD as “provocative and anti-communist.” The poetess is having a hard time with the inability to publish, she writes a lot “on the table”, the motives of her poetry change from romantic to social. After the arrest of her husband and son, Akhmatova begins work on the poem “Requiem”. The “fuel” for creative frenzy was soul-exhausting worries about loved ones. The poetess understood perfectly well that under the current government this creation would never see the light of day, and in order to somehow remind readers of herself, Akhmatova writes a number of “sterile” poems from the point of view of ideology, which, together with censored old poems, make up the collection “Out of Six books", published in 1940.

Latest published collection Anna Andreevna dates back to 1924. After this, her poetry came to the attention of the NKVD as “provocative and anti-communist.” The poetess is having a hard time with the inability to publish, she writes a lot “on the table”, the motives of her poetry change from romantic to social. After the arrest of her husband and son, Akhmatova begins work on the poem “Requiem”. The “fuel” for creative frenzy was soul-exhausting worries about loved ones. The poetess understood perfectly well that under the current government this creation would never see the light of day, and in order to somehow remind readers of herself, Akhmatova writes a number of “sterile” poems from the point of view of ideology, which, together with censored old poems, make up the collection “Out of Six books", published in 1940.

All Second world war Akhmatova spent time in the rear, in Tashkent. Almost immediately after the fall of Berlin, the poetess returned to Moscow. However, there she was no longer considered a “fashionable” poetess: in 1946, her work was criticized at a meeting of the Writers' Union, and Akhmatova was soon expelled from the Union of Writers. Soon another blow falls on Anna Andreevna: the second arrest of Lev Gumilyov. For the second time, the poetess’s son was sentenced to ten years in the camps. All this time, Akhmatova tried to get him out, wrote requests to the Politburo, but no one listened to them. Lev Gumilyov himself, knowing nothing about his mother’s efforts, decided that she had not made enough efforts to ![]() help him, so after his release he moved away from her.

help him, so after his release he moved away from her.

In 1951, Akhmatova was reinstated in the Union Soviet writers and she is gradually returning to active creative work. In 1964, she was awarded the prestigious Italian literary prize "Etna-Torina" and she is allowed to receive it because the times of total repression have passed, and Akhmatova is no longer considered an anti-communist poet. In 1958 the collection “Poems” was published, in 1965 - “The Running of Time”. Then, in 1965, a year before her death, Akhmatova received a doctorate from Oxford University. Anna Andreevna Akhmatova died on March 5, 1966 in Domodedovo near Moscow.

Akhmatova's main achievements

1912 - collection of poems “Evening”

1914-1923 - a series of poetry collections “Rosary”, consisting of 9 editions.

1917 - collection “White Flock”.

1922 - collection “Anno Domini MCMXXI”.

1935-1940 - writing the poem “Requiem”; first publication - 1963, Tel Aviv.

1940 - collection “From Six Books”.

1961 - collection of selected poems, 1909-1960.

1965 - the last lifetime collection, “The Running of Time.”

Interesting facts from the life of Akhmatova

Throughout her life, Akhmatova kept a diary, excerpts from which were published in 1973. On the eve of her death, going to bed, the poetess wrote that she was sorry that her Bible was not here, in the cardiological sanatorium. Apparently, Anna Andreevna had a presentiment that the thread of her earthly life was about to break.

In Akhmatova’s “Poem without a Hero” there are the lines: “clear voice: I am ready for death.” These words sounded in life: they were spoken by Akhmatova’s friend and comrade-in-arms in the Silver Age, Osip Mandelstam, when he and the poetess were walking along Tverskoy Boulevard.

After the arrest of Lev Gumilyov, Akhmatova, along with hundreds of other mothers, went to the notorious Kresty prison. One day, one of the women, exhausted by anticipation, seeing the poetess and recognizing her, asked, “Can you describe this?” Akhmatova answered in the affirmative and it was after this incident that she began working on Requiem.

Before her death, Akhmatova nevertheless became close to her son Lev, who for many years harbored an undeserved grudge against her. After the death of the poetess, Lev Nikolaevich took part in the construction of the monument together with his students (Lev Gumilyov was a doctor at Leningrad University). There was not enough material, and the gray-haired doctor, along with the students, wandered the streets in search of stones.

Akhmatova (pseudonym; real name- Gorenko) Anna Andreevna, Russian Soviet poetess. Born into the family of a naval officer. She studied at the Higher Women's Courses in Kyiv and at the Faculty of Law of Kyiv University. From 1910 she lived mainly in St. Petersburg. In 1912, A.’s first book of poems, “Evening,” was published, followed by the collections “The Rosary” (1914), “The White Flock” (1917), “Plantain” (1921), and others. A. joined the group of Acmeists (see Acmeism ). In contrast to the Symbolists, with their craving for the otherworldly, foggy, A.’s lyrics grew on real, life-based soil, drawing from it the motives of “great earthly love.” Contrast - distinguishing feature her poetry; melancholic, tragic notes alternate with bright, jubilant ones.

Briefly about yourself:

I was born on June 11 (23), 1889 near Odessa (Bolshoi Fontan). My father was at that time a retired naval mechanical engineer. As a one-year-old child I was transported north - to Tsarskoe Selo. I lived there until I was sixteen.

My first memories are of Tsarskoye Selo: the green, damp splendor of the parks, the pasture where my nanny took me, the hippodrome where small colorful horses galloped, the old train station and something else that was later included in the “Ode of Tsarskoye Selo”.

I spent every summer near Sevastopol, on the shore of Streletskaya Bay, and there I became friends with the sea. The most powerful impression of these years was the ancient Chersonesus, near which we lived.

I wrote my first poem when I was eleven years old. Poems began for me not with Pushkin and Lermontov, but with Derzhavin (“On the Birth of a Porphyry-Born Youth”) and Nekrasov (“Frost, Red Nose”). My mother knew these things by heart.

I studied at the Tsarskoye Selo women's gymnasium. At first it’s bad, then much better, but always reluctantly.

In 1905, my parents separated, and my mother and children went south. We whole year We lived in Yevpatoria, where I took my penultimate class at the gymnasium at home, yearned for Tsarskoye Selo and wrote a great many helpless poems. The echoes of the revolution of the fifth year reached dully Evpatoria, cut off from the world. The last class took place in Kyiv, at the Fundukleevskaya gymnasium, from which she graduated in 1907.

I entered the law faculty of the Higher Women's Courses in Kyiv. While I had to study the history of law and especially Latin, I was happy, but when purely legal subjects began, I lost interest in the courses.

The laying of new boulevards along the living body of Paris (which Zola described) was not yet completely completed (Boulevard Raspail). Werner, a friend of Edison, showed me two tables at the Taverne de Pantheon and said: “And these are your Social Democrats, here are the Bolsheviks, and there are the Mensheviks.” Women, with varying success, tried to either wear pants (jupes-cullottes) or almost swaddle their legs (jupes-entravees). Poems were in complete disrepair, and they were bought only because of the vignettes of more or less famous artists. I already understood then that Parisian painting had eaten up French poetry.

Having moved to St. Petersburg, I studied at Raev’s Higher Historical and Literary Courses. At this time I was already writing poems, which were later included in my first book.

When they showed me the proof of “The Cypress Casket” by Innokenty Annensky, I was amazed and read it, forgetting everything in the world.

In 1910, a crisis of symbolism clearly emerged, and aspiring poets no longer joined this movement. Some went to futurism, others to acmeism. Together with my comrades in the First Workshop of Poets - Mandelstam, Zenkevich, Narbut - I became an Acmeist.

I spent the spring of 1911 in Paris, where I witnessed the first triumphs of Russian ballet. In 1912 she traveled through Northern Italy (Genoa, Pisa, Florence, Bologna, Padua, Venice). The impression of Italian painting and architecture was enormous: it was like a dream that you remember all your life.

In 1912, my first collection of poems, Evening, was published. Only three hundred copies were printed. Criticism reacted favorably to him.

In March 1914, the second book, “The Rosary,” was published. She was given approximately six weeks to live. At the beginning of May, the St. Petersburg season began to fade, everyone was gradually leaving. This time the separation from St. Petersburg turned out to be eternal. We returned not to St. Petersburg, but to Petrograd, from the 19th century we immediately found ourselves in the 20th, everything became different, starting with the appearance of the city. It seemed that the small book of love poetry by the novice author was about to drown in world events. Time decreed otherwise.

I spent every summer in the former Tver province, fifteen miles from Bezhetsk. This is not a picturesque place: fields plowed in even squares on hilly terrain, mills, swamps, drained swamps, “gates”, bread, bread... There I wrote many poems of “The Rosary” and “The White Flock”. "The White Flock" was published in September 1917.

Readers and critics are unfair to this book. For some reason it is believed that she had less success than "rosary beads". This collection appeared under even more dire circumstances. Transport froze - the book could not be sent even to Moscow, it was all sold out in Petrograd. Magazines were closed, newspapers too. Therefore, unlike the Rosary, the White Flock did not have a noisy press. Hunger and devastation grew every day. Oddly enough, now all these circumstances are not taken into account.

After October Revolution I worked in the library of the Agronomic Institute. In 1921, a collection of my poems, “Plantain,” was published, and in 1922, the book “Anno Domini.”

Around the mid-20s, I began to study very diligently and with great interest the architecture of old St. Petersburg and the study of the life and work of Pushkin. The result of my Pushkin studies were three works - about “The Golden Cockerel”, about “Adolphe” by Benjamin Sonstan and about “The Stone Guest”. All of them were published at one time.

The works “Alexandrina”, “Pushkin and the Nevskoe seaside”, “Pushkin in 1828”, which I have been working on for almost twenty years recent years, apparently, will be included in the book “The Death of Pushkin”.

Since the mid-20s, my new poems have almost stopped being published, and my old ones have almost stopped being reprinted.

The Patriotic War of 1941 found me in Leningrad. At the end of September, already during the blockade, I took a plane to Moscow.

Until May 1944, I lived in Tashkent, eagerly catching news about Leningrad, about the front. Like other poets, she often performed in hospitals and read poems to wounded soldiers. In Tashkent, I first learned what the shadow of a tree and the sound of water are like in scorching heat. I also learned what human kindness is: in Tashkent, I was seriously ill a lot.

In May 1944, I flew to spring Moscow, already full of joyful hopes and anticipation of an imminent victory. In June she returned to Leningrad.

The terrible ghost pretending to be my city amazed me so much that I described my meeting with him in prose. At the same time, the essays “Three Lilacs” and “Visiting Death” appeared - the latter about reading poetry at the front in Teriokki. Prose has always seemed both mysterious and seductive to me. From the very beginning I knew everything about poetry - I never knew anything about prose. Everyone praised my first experience, but, of course, I didn’t believe it. I called Zoshchenka. He ordered some things to be removed and said that he agreed with the rest. I was glad. Then, after her son’s arrest, she burned it along with the entire archive.

I have long been interested in issues of literary translation. In the post-war years I translated a lot. I'm still translating it now.

In 1962, I finished “Poem without a Hero,” which I wrote for twenty-two years.

Last spring, on the eve of Dante's year, I again heard the sounds of Italian speech - I visited Rome and Sicily. In the spring of 1965, I went to the homeland of Shakespeare, saw the British sky and the Atlantic, saw old friends and met new ones, and visited Paris again.

I didn't stop writing poetry. For me, they contain my connection with time, with new life my people. When I wrote them, I lived by the rhythms that sounded in the heroic history of my country. I am happy that I lived during these years and saw events that had no equal.

Anna Andreevna Akhmatova, real name Gorenko, after the marriage of Gorenko-Gumilyov (born June 23, 1889, 11th Old Style, in the Bolshoy Fontan dacha area near Odessa; died March 5, 1966 in the Podmoskovye sanatorium near the city of Domodedovo, Moscow region) - classic of Russian poetry.

Anna Akhmatova was born near Odessa to engineer-captain 2nd rank Andrei Antonovich Gorenko and his wife Inna Erasmovna (nee Stogova), who soon moved to Tsarskoye Selo (1891), where in 1900 Anna Gorenko entered the Tsarskoe Selo Mariinsky Gymnasium. During her studies, she met her future husband, Nikolai Gumilyov (1903).

In 1906-1907 Anna lived in Kyiv, where, after graduating from high school, she entered the Higher Women's Courses. In 1909, she accepted Gumilyov’s official proposal to become his wife, and on April 25, 1910 they got married. In 1911 Anna came to St. Petersburg, where she continued her education at the Higher Women's Courses. During this period, she met Blok, and her first publication appeared under the pseudonym Anna Akhmatova. Fame came to Akhmatova after the publication of the poetry collection "Evening" in 1912, after which the next collection "Rosary" was published in 1914, and in 1917 "The White Flock". In the fall of 1918, after a break with Gumilyov, who returned from London to Petrograd, Anna Akhmatova married the orientalist V.K. Shileiko.

In April 1921, the 4th collection of poems, “Plantain,” was published. On August 25, 1921, Akhmatova’s first husband, Gumilev, was shot in the fabricated Tagantsev case near the village of Berngardovka near Petrograd. In October, the 5th collection of poems "Anno Domini" (Latin) appeared. In 1922, having separated from Shileiko, Akhmatova married art critic Nikolai Punin, with whom she lived for the next 15 years. Beginning in 1922, Anna Akhmatova’s books were subject to strict censorship, and in 1924 they were no longer published. In the fall of 1924, Akhmatova moved to Punin, in the inner (garden) wing of the Sheremetyev Palace (Fountain House - now the Anna Akhmatova Museum). Here, on October 24, 1935, Nikolai Punin, together with a group of students from Leningrad University, including Akhmatova’s son, Lev Gumilyov, were arrested. Thanks to the support of Anna Akhmatova's friends Bulgakov, Pasternak, Pilnyak, her husband and son were released after appealing to Stalin. In January 1936, Akhmatova, together with Pasternak, went to the USSR prosecutor's office with a request to mitigate the fate of Mandelstam, who in May 1937, after exile, was able to return to Moscow. In March 1938, Akhmatova's son was arrested again and sentenced to 10 years in the camps in 1939; In May 1938, Mandelstam was arrested and exiled, and soon died of typhus in a transit camp near Vladivostok. In May 1940, Akhmatova’s collection “From Six Books” was published in Leningrad. In August, Anna Akhmatova began work on “Poem without a Hero.”

With the outbreak of war and famine in besieged Leningrad, Anna Akhmatova was evacuated to Moscow, then to Chistopol, from where she and her family K.I. Chukovsky she came to Tashkent, where in May 1943 she published a collection of poetry. In the summer of 1944, Akhmatova returned to Leningrad. At the end of 1945, Anna Akhmatova hosted the English philosopher and historian Isaiah Berlin at the Fountain House. This meeting probably served as one of the reasons for the notorious statement of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks about the magazines “Zvezda” and “Leningrad”, in which the work of Akhmatova and Zoshchenko, as ideologically alien, was defamed. Soon after this, both writers were expelled from the Union of Soviet Writers. In 1949, Nikolai Punin and Lev Gumilyov were arrested again and sentenced to 10 years in labor camp.

In 1951, Anna Akhmatova was reinstated in the Writers' Union. At the beginning of 1955, the Leningrad branch of the Literary Fund allocated Akhmatova a country house in the writer's village of Komarovo. Her works began to be published in the USSR and abroad. In 1962, Akhmatova was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature; On December 12, 1964 in Rome she received the prestigious literary prize "Etna-Taormina"; 5 June 1965 - honorary degree of Doctor of Letters from Oxford University. In October 1965, Akhmatova’s last lifetime collection of poems, “The Running of Time,” was published. In November, Akhmatova suffered her 4th heart attack, after which she went to a cardiological sanatorium near the city of Domodedovo. Here, on the morning of March 5, 1966, at the age of 76, Anna Akhmatova died. On March 10, after the funeral service in St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral in Leningrad, she was buried in the cemetery in Komarovo.